This Tuesday, October 24th, marked 20 years since the final supersonic passenger flight. On that day in 2003, the British Airways Concorde with registration G-BOAG flew from New York (JFK) and landed at 4:05 pm at Heathrow Airport in London for the last time, ending more than 27 years of commercial services.

The decommissioning of the Concorde meant a setback for air travel, which had evolved rapidly since the end of the Second World War.

In the context of the Cold War, the British and French came together to compete against the Americans (Boeing 2707 and Lockheed L-200) and Soviets (Tupolev TU-144) for the primacy of supersonic aircraft.

The English had the Bristol Type 223 project and the French had the idea of the Super Caravelle. In 1962, the programs were unified and the Concorde project emerged under the future leadership of the manufacturers Aerospatiale and BAC.

Follow ADN: Instagram | Twitter | Facebook

The first interested parties were announced on June 3, 1963, Air France and BOAC (which would become British Airways after the union with BEA), in addition to Pan Am, the airline that dictated the direction of global aviation.

The Concorde was the protagonist of one of the best-known industrial espionage cases of the Cold War, when KGB agents stole information from the project and took it to the Soviet Union. And it was up to the Tupolev TU-144 to perform the first flight of a supersonic commercial aircraft, on December 31, 1968.

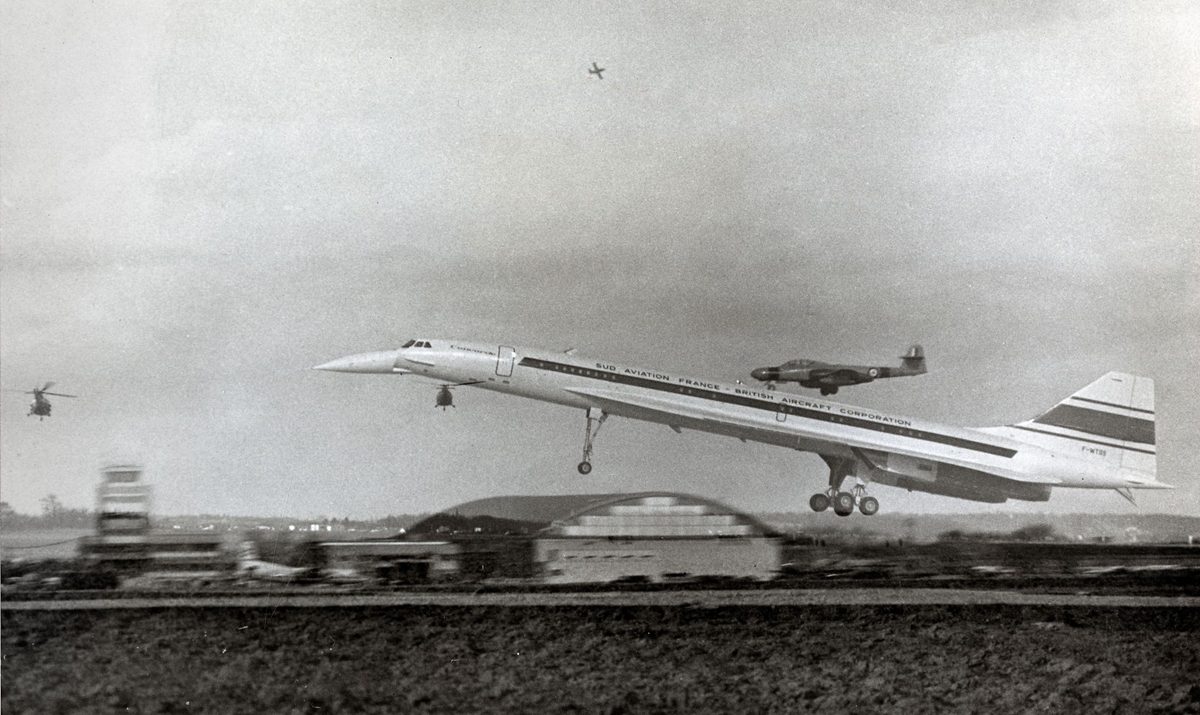

Concorde made its first flight on March 2, 1969 in Toulouse, in the south of France, with Sud Aviation’s chief pilot, André Turcaut, in command, along with first officer Jacques Guinard and flight engineers Henri Perrier. and Michel Rétif.

The plane’s prospects looked promising, with 74 aircraft booked by that date, coming from carriers such as Air France, BOAC, Japan Air Lines, Lufthansa, Qantas and TWA. The number would reach 78 aircraft in 1972 with the addition of CAAC and Iran Air.

No supersonic flights over the US

Of the supersonic programs at the time, Concorde was the most advanced, while the Soviet jet faced technical problems and the Americans dropped out of the race when the US Congress cut funding for the program after burning through hundreds of millions of dollars.

This meant that Concorde would be the only Western model, however, environmental groups started a campaign calling for a ban on Concorde flights, due to the “Sonic Boom” caused by the breaking of the sound barrier.

In a controversial move, the US Congress banned Concorde from flying over populated areas at supersonic speed. The measure affected Aerospatiale/BAC’s propaganda about the advantages of Concorde’s supersonic flights.

Contrary to common sense, it was not just the oil crisis that was responsible for the program’s fiasco, but economic issues. As the Concorde’s costs rose, the fares that airlines had to charge also became more expensive, and the early 1970s were particularly difficult for the world’s leading airline, Pan Am, which was unable to fill its shiny Boeing 747s.

Doing the math, Pan Am executives concluded that the aircraft would not be profitable on the main routes and feared going into more debt to buy the Concorde.

On January 31, 1973, Pan Am canceled its supersonic orders, after other airlines had already given up on the plane before such as Air Canada and United Airlines. But Pan Am’s decision not to buy the plane was a major blow to Concorde’s image.

The reason is that the most global airline in the world at the time was a reference for its rivals in terms of fleet. Without Concorde at Pan Am, they felt free from having to operate supersonic to remain competitive.

In addition to Air France and BOAC, only Air China, Air India, Iran Air and Qantas remained as future operators, which would later cancel orders or let the protocols of intent expire.

The hopes of Air France and now British Airways, BOAC’s successor, were to operate the Concorde on flights to the East Coast of the United States for several reasons: the transatlantic market was the most profitable, there were no range restrictions and because it took place in the largest part of the journey over the ocean, there were no restrictions on the supersonic boom.

The American government authorized, on a provisional basis, regular Concorde operations at Washington Dulles (IAD) and at John F. Kennedy (JFK), in New York.

Dulles Airport complied with federal authorities’ decision, but the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, JFK’s owner, denied operations, citing environmental concerns. One of the backgrounds was the country’s protectionism as it did not have a local product to compete with the plane.

Revenue flights

With aircraft received from December 1975 onwards, Air France and British Airways had to look for other destinations to operate the supersonic.

For Air France, the route chosen was Paris (CDG)-Dakar-Rio de Janeiro (GIG) and for British Airways, the London (LHR)-Bahrain flight. For the French, Brazil was one of the fastest growing countries in the world and with strong economic ties with France. British Airways envisioned Bahrain as a stopover for flights to Singapore.

On January 21, 1976, at exactly the same time, the first commercial Concorde flights took off respectively from Paris and London: AF805, operated by F-BVFA and with a crew led by Pierre Chanoine and Pierre Dudal, and BA300, operated by G -BOAA, led by Captain Norman Todd. The ceremony in Paris was held on Satellite 5 and was attended by ambassadors from Brazil, England and Senegal, as well as French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing.

After Dakar/Rio de Janeiro and Bahrain, Caracas, in Venezuela, was the next destination served by the supersonic, on April 9, 1976, with a weekly Air France flight via Santa Maria, in the Azores. Flights to Washington began on May 24 of the same year, three weekly frequencies for each company.

Air France operated charter flights for Iran Air between Paris, Kish Islands and Tehran as part of the Iranian airline’s plans to operate the plane. The much-desired operation in New York was authorized in 1977, with both companies inaugurating services on November 22nd.

On December 9, 1977, British Airways extended the route from Bahrain to Singapore through a partnership with Singapore Airlines. The G-BOAD aircraft received the Singapore Airlines livery on the left side, but the flights only lasted until the 13th of the same month, due to Malaysia prohibiting the aircraft from flying over the Strait of Malacca. Service would only be restored on January 24, 1979.

On September 20, 1978, Air France extended the flight from Washington to Mexico City (MEX), twice a week, with the Concorde flying subsonic over Florida.

Of the unusual operations, the agreement between the two Europeans with Braniff International Airways was the most notorious. Starting in December 1978, Braniff operated the Concorde on subsonic flights between Washington and Dallas/Fort Worth, in one of company president Harding Lawrence’s marketing moves.

Because these were foreign aircraft operating domestic flights, Braniff had to change the aircraft’s registration plates every time it entered or left the United States and maintain documentation on board the aircraft. The flights operated with less than 20% occupancy and were canceled in May 1980.

Air France operations to Brazil and Venezuela were canceled in April 1982 and in October it was the turn of flights to Washington and Mexico City.

British Airways extended flights from Washington to Miami in March 1984. Both destinations were canceled in January 1991. In the end, New York was the only destination that had commercial services by both companies and in the peak season British Airways operated London -Bridgetown, Barbados, on Saturdays, and flights to Toronto.

Phil Collins on the UK-US airlift during Live Aid

Flying on Concorde, whether as a passenger or crew, was the most exclusive experience in commercial aviation. Connecting the most influential cities in the world, the presence of millionaires and celebrities was common in which time was the crucial factor and the plane began to have its own vocabulary among its frequenters, such as ‘I’ll Concorde to New York tomorrow’ or ‘ Are you Concorde from Paris’?

To increase revenue, airlines carried out exotic charter flights, such as trips around the world with the supersonic and double New Year’s celebrations, with passengers celebrating New Year’s Eve in Paris or London, then flying the aircraft against the time zone, and “going back in time”, to the point of arriving in New York in time to see New Year’s Eve again.

The “journey through time” was one of the highlights of Live Aid, a musical show that took place in England and the United States on July 13, 1985, with the aim of raising funds for poor countries in Africa.

Singer Phil Collins gave a performance in London and from there went to Heathrow by helicopter, taking a Concorde to New York and concluding the trip with another helicopter to Philadelphia, where he performed another show as part of the famous concert.

Over time, the supersonic plane frenzy diminished until it became an everyday occurrence on flights between Paris, London and New York.

However, this routine would end on July 25, 2000 when the Air France F-BTSC Concorde crashed after taking off from Charles de Gaulle Airport, in Paris, heading to New York with a charter of German retirees who were going to participate in a cruise.

The cabin crew heard a loud bang during takeoff and the loss of the engine shortly after V1 – the speed at which the takeoff could no longer be aborted.

Unaware that the fuel tank on the left side was on fire, the crew struggled to control the plane and even considered landing at Le Bourget Airport, however the supersonic plane lost lift and crashed into a hotel in Gonesse, killing the 109 occupants of the plane. plane and four people on the ground.

Toshihiko Sato, a passenger on board an Air France 747, took a photo of the F-BTSC taking off in flames. The image would appear on the cover of several newspapers, and on television, a video of the plane in flight, taken by an amateur cameraman, was shown. They are the only two media outlets that recorded the accident.

Subsequently, investigations showed that the supersonic plane hit a titanium bar that fell from Continental Airlines DC-10-30 N13067, which had taken off minutes earlier. At high speed, the bar hit the tires to the point of generating a shock wave that affected tank number five and the electrical circuits, causing the aircraft to catch fire.

Immediately, Air France and British Airways suspended Concorde operations until necessary modifications were made to improve safety.

On November 7, 2001, the plane returned to commercial operations, but the scenario was not as favorable as before. The scenes of the Concorde in flames and, mainly, the drop in air traffic after ‘9/11’ meant that Concorde operations did not have the appeal of other times and so, on April 10, 2003, the two airlines announced the termination of supersonic operations.

Sir Richard Branson, owner of Virgin Atlantic, even made a public offer to buy British Airways planes “for the same price they paid”, one pound, a symbolic amount paid to the British government. Then the offer rose to a million pounds per plane until it reached 5 million pounds, but the British airline refused to sell them.

Air France made its last commercial flight on May 31, 2003, with the F-BTSD arriving in Paris (CDG) after taking off from New York.

British Airways went a step further and ceased operations on October 24th, when the G-BOAG took off from JFK to London (LHR). The aircraft returned to the USA on November 5, to be displayed at Boeing Field, in Seattle.

Concorde’s final flight took place on November 26, 2003 when the G-BOAF jet left Heathrow and landed at Bristol-Filton Airport, where it was displayed at the Aerospace Bristol museum.

Supersonic flights back soon?

After the end of Concorde operations, several projects attempt to recreate supersonic flights, using a smaller plane to serve the VIP public. The best-known project is the Boom Supersonic Overture, with capacity for up to 80 passengers and 7,000 km of range.

Despite having orders from American Airlines, United Airlines and a purchase commitment from Japan Airlines, the project still has many challenges ahead before it becomes a reality.

In the end, the Concorde represented the last chapter in a series of technological advances in post-war aviation. If a Rio-Paris flight previously took three stops and lasted 24 hours in 1946, 30 years later it was possible to make the journey with one stopover and in 7 hours.

Concorde’s elegant profile, which resembled a bird of prey during takeoff and landing operations, will remain a symbol of a desire that has not yet been fulfilled in aviation: that of supersonic flights accessible to all.